This will come as a surprise to no one: I am white. Though that’s never been a surprise to me, I have never been so aware of my whiteness as I am while living on the outskirts of Harlem. I confront my whiteness every day.

I try to be conscientious and introspective about my identity. I want to acknowledge my whiteness, and in so doing, I must acknowledge my privilege. I do not feel defensive about my privilege. Acknowledging my privilege doesn’t mean that I was lazy, and it doesn’t mean that I didn’t work hard, and it doesn’t mean that I haven’t earned my spot at Columbia. It simply means that I was in a system that was engineered for people like me to thrive. Perhaps most importantly right now, it means that I can walk basically anywhere in the United States and not fear that I will be accused of a crime. It’s ok to acknowledge those things. It doesn’t hurt me to acknowledge that these privileges exist.

What hurts is that these privileges don’t exist for everyone.

I’ll be honest, I haven’t always understood systemic racism. Growing up in the largely homogenous Little-town that I did, I was told that racism was calling people bad names, profiling them, and judging them based on their skin color. There wasn’t a lot of opportunity to interact with people of other races, and we all seemed to share the culture of “suburb,” so I didn’t see the type of racism my elementary school teachers warned me about, and we only talked about it vague abstractions in my English classes.

I’ve had to do a lot of learning about racism since I moved to New York, and while I’m embarrassed that it took me this long, I am at least glad that I am willing to learn. I am still constructing my role and listening to what it means to be a genuine white ally. I’m willing to stand corrected if I find I am not actually being helpful.

I do think that there are more people out there like me; people who have honest, real desires to be allies to the Black community, and not in a white savior-y sort of way, but in a genuine way. I think because the nature of the conversation is a bit virulent at times, it can be difficult to know what to do or how to go about being an ally.

I’m not an expert in issues of diversity, and I want it to be clear that I can’t call myself an expert for a thousand reasons, but most importantly because I can only conceptualize what it feels like to be racially profiled, I can only conceptualize what it feels like to lose a son or a daughter to racial tension, I can only conceptualize what it means to be diverse.

I’m not an expert, but I am a human. I am a human deeply, deeply troubled by what happened this week to Alton Sterling and Philando Castile (say their names). (Here are some links if you’ve missed them. They come with a significant trigger warning: Philando Castile and Alton Sterling).

And because I am a human, grappling for ways to be a human, and grappling to support a community in pain, I wish to publish some of the things I am piecing together about being a white ally. My hope is that role becomes more defined for myself, but also for others who have had similar considerations. Most importantly, I hope that the gap between white and black can heal, and that true equality can come to exist for America.

Steps To Becoming a White Ally from a Person in the Beginning Phase

- Educate yourself. I learned this lesson in an unforgettable way. I went to a round table discussion on race at Teachers College, and commented vaguely about how it would be nice for students of color to share their stories with us so that we could have more empathy. I got DE-NIED. A student responded, eloquently and respectfully as follows: “It is not the duty of the oppressed to educate the oppressors.”Jesse Williams said something similar at the BET awards (if you haven’t watched his speech, I urge you to please do it with an open heart. He’s a former English teacher, so he writes and speaks with the

best ethos, pathos, and logos you’ve heard in a long time). Williams said, “The burden of the brutalized is not to comfort the bystander.” The semantics are different here than what the woman at the roundtable told me, and that role of the bystander is semantically different than that of an oppressor. But I felt so surprised by that woman’s comment, that I was being lumped in the oppressor role, that it was not her job to educate me. And while I still don’t think I am a blatant oppressor of black people, it was a worthwhile question to ask myself if I was, or what ways I was quietly, accidentally one. More importantly, I could examine how white machinery might be oppressive. Most importantly, I realized that to ask her to sit down and give me a crash course on her experience took the burden off of me and put it onto her to help me. SO much work has been done to record the black experience already. If I genuinely care about equality, then I need to be willing to learn a little on my own. Inevitably, being present for the discussion lets me be privy to a slew of stories that build my empathy and solidarity for the black community, but those who shared didn’t share solely for my measly benefit, more so from an authentic need to be understood and heard.

Listen instead of instruct. The example above taught me this as well. Here I was, in a room full of people of color offering suggestions for ways to improve racial problems in America. The absurdity of it now is not lost on me. It was part of a knee jerk reaction that I think many of us feel to solve a problem, but this isn’t one that can be healed with a simple solution Band-aid (which, incidentally, only come in white “skin color”).To quote Jesse Williams again, “If you have a critique for the resistance, for our resistance, then you better have an established record of critique for our oppression. If you have no interest in equal rights for black people then do not make suggestions to those who do. Sit down.” Sure, you could choose to be offended by Williams’ strong language, as some were, or you could choose to listen instead of instruct. Realize that the solutions that have worked for white people to prosper might be different than solutions for the black community. Realize that you don’t have to know the answer on another group’s behalf. The more you listen, the clearer your role becomes as an ally.

Listen instead of instruct. The example above taught me this as well. Here I was, in a room full of people of color offering suggestions for ways to improve racial problems in America. The absurdity of it now is not lost on me. It was part of a knee jerk reaction that I think many of us feel to solve a problem, but this isn’t one that can be healed with a simple solution Band-aid (which, incidentally, only come in white “skin color”).To quote Jesse Williams again, “If you have a critique for the resistance, for our resistance, then you better have an established record of critique for our oppression. If you have no interest in equal rights for black people then do not make suggestions to those who do. Sit down.” Sure, you could choose to be offended by Williams’ strong language, as some were, or you could choose to listen instead of instruct. Realize that the solutions that have worked for white people to prosper might be different than solutions for the black community. Realize that you don’t have to know the answer on another group’s behalf. The more you listen, the clearer your role becomes as an ally. - Don’t expect anyone to pat you on the back and give you cookies for showing up. You don’t get a medal for altruism for going to a round table or for starting an inclusive conversation on Facebook. As my sister, Kristy put it, “You don’t get cookies for doing what needs to be done and you especially don’t get cookies simply for not (accidentally or purposefully) hating other humans.” Instead of expecting refreshments, prepare to roll your sleeves up instead and do the self-work. Be prepared to address that racism that has dogged you throughout your life, perhaps unknowingly. Don’t get me wrong, it’s good and important that you’re there. But it should be a fundamental of humanity that we look out for each other rather than something that deserves brownie points for (or cookie points, as the case may be).

- If you extend the benefit of the doubt to the white parties involved (especially in issues of police brutality), also be willing to extend the benefit of the doubt to black parties involved in any scuffle. Notice who you are naturally inclined to defend and why. Think about the mental gymnastics that led you to justifying whatever choice this person made. Then, because it’s good form, good critical thinking, and a good exercise in empathy, apply the same thought process to the other side.

- Realize that there are systems in America that (perhaps inadvertently) have favored a white dominant culture. Systemic Racism made the most sense to me when I read bell hooks’ book, Teaching to Transgress. She is a brilliant writer and thinker, and in her book, she discusses what it was like for the schools to integrate when she was young. In her experience, before integration, her teachers were passionate encouragers of critical thinking, introspection, and challenging existing ideals. However, when she was, “bussed to white schools, we soon learned that obedience, and not a zealous will to learn, was what was expected of us. Too much eagerness to learn could be easily seen as a threat to white authority” (3).

If you are looking at statistics, Richard Milner’s book, Rac(e)ing To Class can confirm what the experience became for minority students, who had been culturally taught in an entirely different way prior to integration. While I was thinking about that, I thought about just how hard an adjustment for me that might be. I also thought about the way that I taught my own students. There were implicit biases in the way I educated my students that favored a white, privileged majority, despite my best intentions! Imagine a school system that is not designed for you to succeed. Imagine how frustrating that would be! Now imagine how much harder it might be to finish high school. And furthermore, what if you’re born into a poor family that needs your help making rent, so you have to work a job in addition to school? Then how much harder is it to finish high school? And how much harder is it to afford or even go to college when your family’s livelihood requires you to contribute actively?

I mean, friends, this is the cusp of the systemic racism rabbit hole, but as an educator trying to understand privilege, this helped me best conceptualize the reality of it. So before you judge a crime, poverty, or housing, or culture, try to think about the system that might have contributed to oppression. If you believe in the American Dream ladder, ok, but realize that some people were born on the third highest rung, where others were born at the bottom. Realize that its going to be a bit harder for some people to climb, not because of capability, or intelligence, or strength, but because, frankly, they have much further to go.

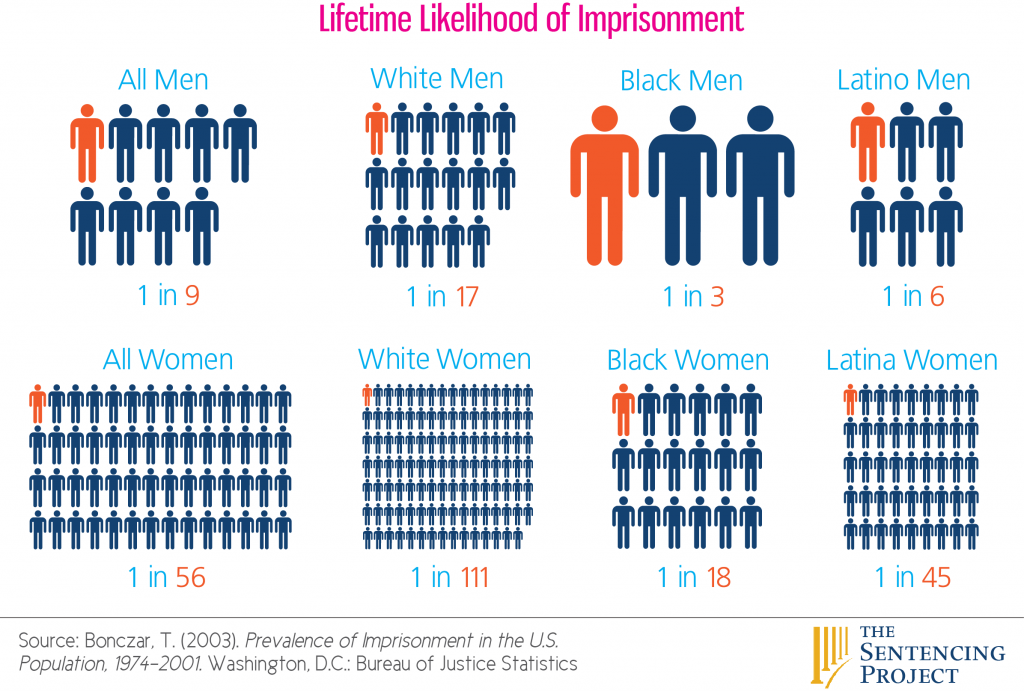

I imagine there are more current statistics, but they illustrate a point here.

- Choose not to be defensive. It’s going to be hard. This is not an emotionless problem America is having, and it’s hard to feel like your good intentions are misunderstood. Many black people in America are angry, and that hurts to hear because it feels so personal. But the harder you listen, the more you will understand why people are angry. You can start to search your own heart and ask, have I accidentally (or implicitly) harbored racist feelings? Have I committed microaggressions that inadvertently lower the self-esteem of someone of a different race? I believe myself to be well-intentioned, but I when I let my defenses down, sure enough, I realized that I have, in fact, contributed to the racial problems in America! Am I embarrassed? Of course! Could I apologize and try harder? Yes! That’s what I think a true white ally should be willing to do. No one has ever personally attacked me, or belittled me, or hated me, even if there was part of my white identity that was hurtful to them.

I think some politicians will have you believe that if the black population is to succeed, it means you or your family will surely fail. I just can’t believe it. Furthermore, I don’t want my family to succeed at the expense of someone else’s. I want to teach my family that love is stronger than money, and that opportunity should exist for all.

It’s not a competition, it’s a country. Let’s start acting like it.

Resources: (These are the resources that have most moved me but I don’t claim that it’s an exhaustive list, but for those of you who are like me, just starting out on the road to ally-ism, I was sure grateful to be pointed in these directions).

-The Dangers of a Single Story by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

–Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

–Teaching to Transgress, bell hooks

-Jesse Williams BET Humanitarian Award Speech

–The Problem with Saying All Lives Matter

On my shelf:

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nahisi Coates.

http://citizenshipandsocialjustice.com/2015/07/10/curriculum-for-white-americans-to-educate-themselves-on-race-and-racism/http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/07/02/civil-rights-act-anniversary-racism-charts_n_5521104.html

The New Jim Crow

I’ve written a dozen comments but erased them all. I just don’t know what to say or think. So thank you for your words and thoughts.

Thank you for your beautiful thoughts Sierra! And for giving direction on the resources, so helpful.

Sierra – As a Mormon, social worker, and concerned citizen in the St. Paul area, I cannot express how grateful I am for your post. It is rewarding to see others who sense with me the responsibility to understand the Black community, and to be OK with hearing their anger. Thank you!

This is exactly what the world needs to hear. Thank you, Sierra. I felt exactly the same way from Littleton to Provo, then DC (where diversity existed for the first time, but I had no idea what to do with it), and now, at Harvard, it’s a topic we are CONSTANTLY talking about. It’s in the Ed School’s mission. Anyway–I really, really appreciate your articulation of both the struggle and the solution. So thank you.